Connecting Theories: An Inclusive Approach to E-commerce Strategy and Digital Business Transformation

This article presents a comprehensive framework that successfully unites popular analyses to inform e-commerce strategy. In particular, you may find the digital business transformation roadmap in section three inspiring.

Executive Summary

Introduction

1. A Comprehensive Framework for Digital Business Strategy

1.1 Phase One: Strategic Analysis

1.2 Phase two: Strategy Formation

2. The Resource and Capability View on Competitive Advantage

3. A Roadmap of Digital Business Transformation (Phase Three)

To Conclude

References

Executive Summary

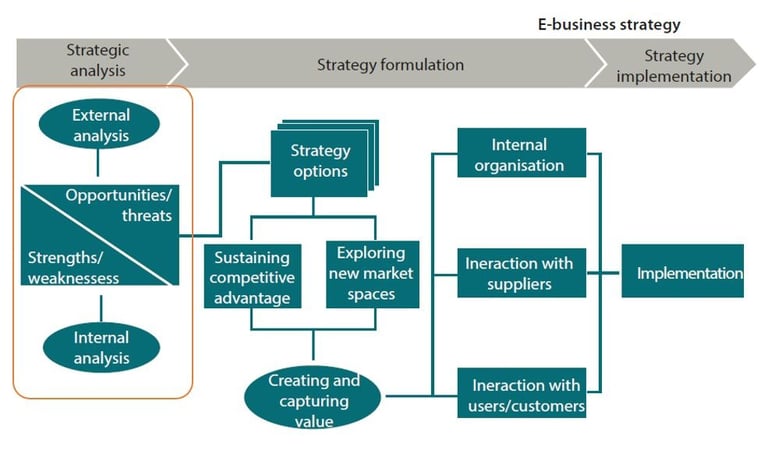

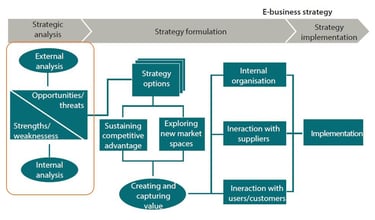

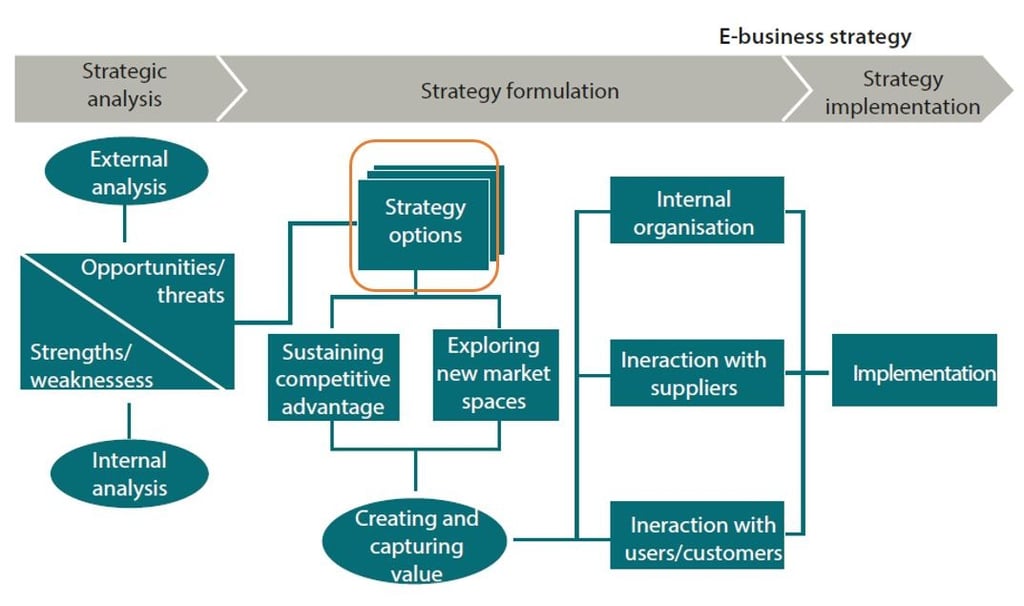

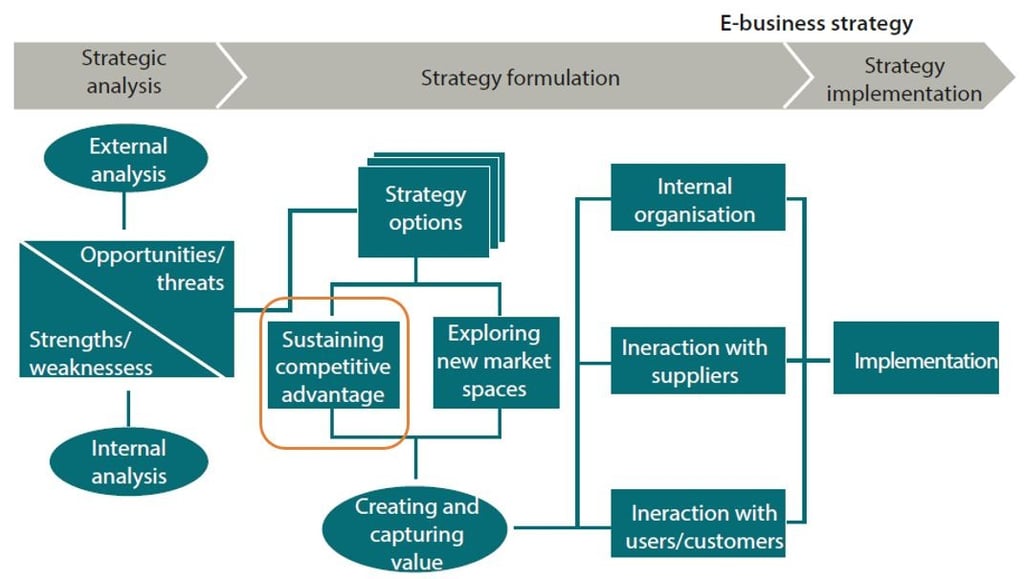

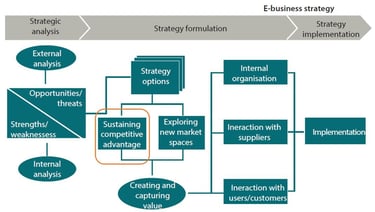

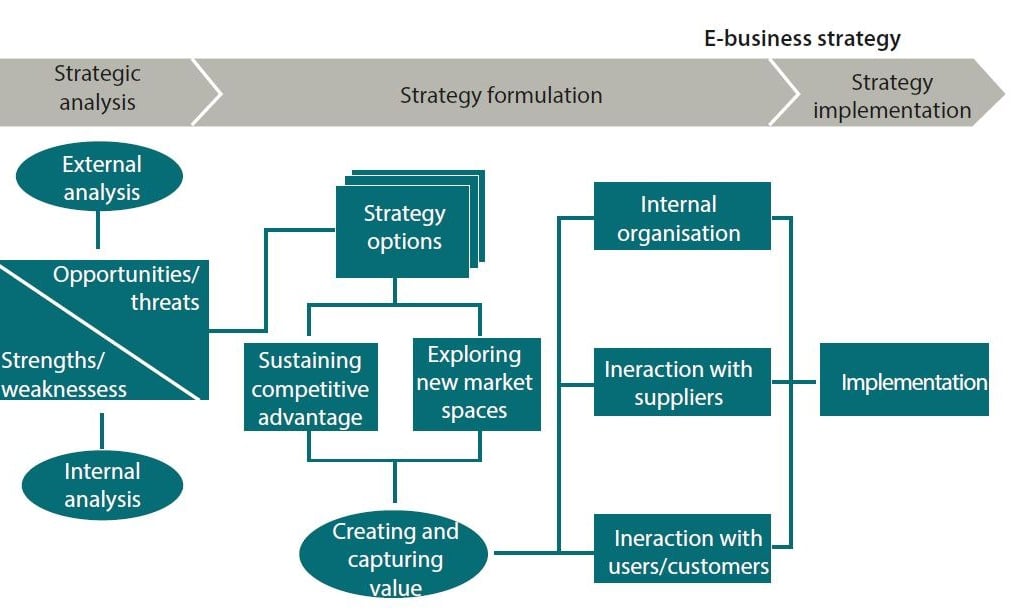

This article first introduces an inclusive ‘E-business Strategy Framework’ (Jelassi et al., 2014) which unites both external and internal marketing analyses to inform e-commerce strategy.

Section two discusses the Resource and Capability based view on business competency. In particular, how integration can be an effective way to sustain the inimitability of core competency through functional alignment and causal ambiguity.

Section three further examines a digital business transformation roadmap, in which I believe certain degrees of integration is inevitable, and thereby, has the potential to create a Strategic Stretch for the company. System acceptance and use is not the last step in a digital transformation process. We need to pay attention to management innovation and value realisation.

Introduction

PESTLE, Porter’s Five Forces, SWOT, Competitive Advantage… these are familiar analyses required for business reports in universities. They may also agree that the frameworks appear to be too segmented. In an extreme case, I once came across a prescribed textbook which categorises them alongside other 90+ ‘essential tools’ for business analytics (Cadle, J., & Turner, P., 2014). A truly puzzling scene.

As I read through some marketing and management textbooks, a question lingers: how can we put together these frameworks to fit in today’s digital world? It seems to me that they are developed in the yesteryear era when e-commerce was still an alternative marketing channel. Nowadays there is hardly any thriving business (including tradespersons) not involved in m/s (mobile/social) commerce. So, I believe there must be a way to weave these frameworks into one single map to guide digital business strategy development.

That's why I felt very delighted coming across the answer in a textbook by Jelassi et al. (2014), Strategies for e-Business: Concepts and Cases on Value Creation and Digital Business Transformation. In the next three sections, I will move on to briefly introduce the book’s key inspirations. They include:

1) A three-phase comprehensive framework for digital business strategy development,

2) The Resource-and-Capability view on e-business competitive advantage, and

3) A roadmap to digital business transformation that echoes my experience.

In section 1, I will explain the ‘e-business strategy framework’. The framework’s first phase successfully unites conventional external/internal marketing analyses in a brilliant SWOT Matrix. For the second phase of the framework, we will follow a trace that leads to the Resource and Capability based view on competitive advantage (section 2). We will see the importance of integration in sustaining a business’ inimitable core competency. Lastly, section 3 presents an implementation roadmap for digital business transformation, along with insights from my personal experiences.

1. A Comprehensive Framework for Digital Business Strategy

1.1 Phase One: Strategic Analysis

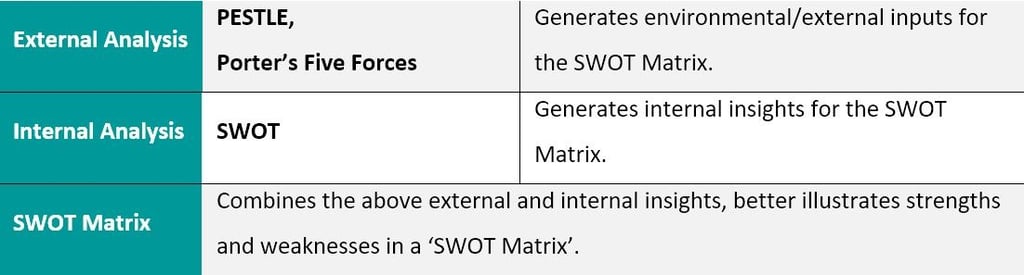

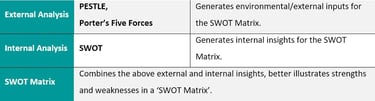

Indeed, this framework is more ideological than practical. But I found it fascinating because it brings together not only the external and internal analysis models but also other theories including competency and an implementation roadmap. Now, let’s have a look at the first phase circled in the above figure – the Strategic Analysis phase. It connects the previously mentioned conventional analysis as shown in the following table.

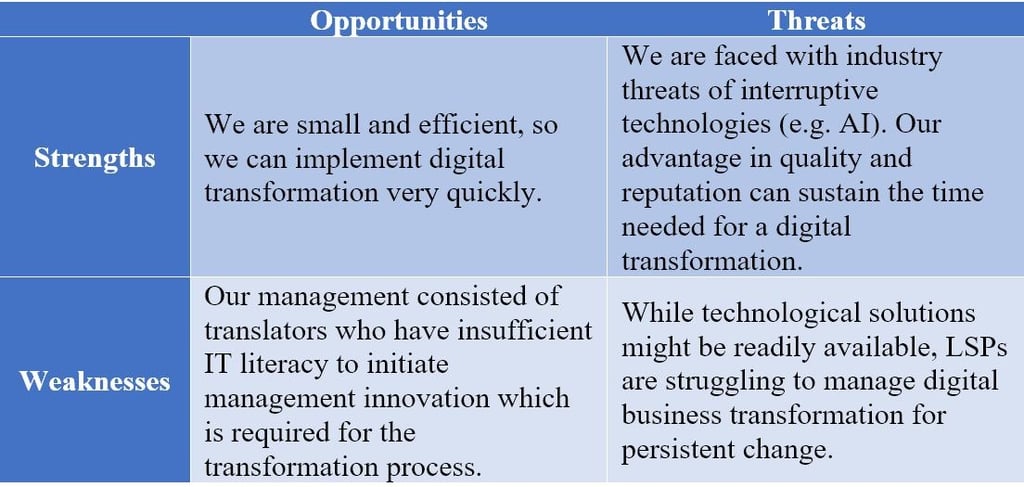

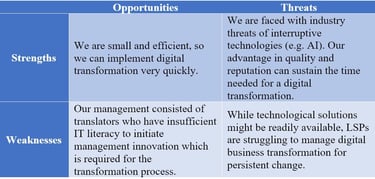

I am going to skip the PESTLE, Porter’s Forces and conventional SWOT analysis and look directly at the SWOT Matrix proposed by Jelassi et al. (2014). The matrix is the key here to unite external and internal findings. Different from the simple four-tile SWOT template, this matrix presents four questions for digital business strategy formulation (figure below). To answer these questions, we can use insights drawn from the external environment/industry analysis (PESTLE, Porter) and internal analysis (SWOT).

I know this looks very theoretical. So let me try to give an example made-up from my past experience. For instance, to answer the four questions raised in the SWOT Matrix, a medium-sized language service provider (LSP) may give answers similar to the table shown below. From PESTLE, Porter’s Five Forces and SWOT analyses (omitted here), we may conclude that the LSP is faced with external opportunities in increased market demand for language translation, and external threats from AI-based online translators; Internally, it has an advantage in its small size with high reputation and a weakness in its translators' technological awareness. As a result, we can weave these findings together into this matrix to answer the four questions as shown below.

1.2 Phase two: Strategy Formation

After weaving together the most popular analytical frameworks in phase one, we move on to the second phase of this model. It is about formulating a digital business strategy.

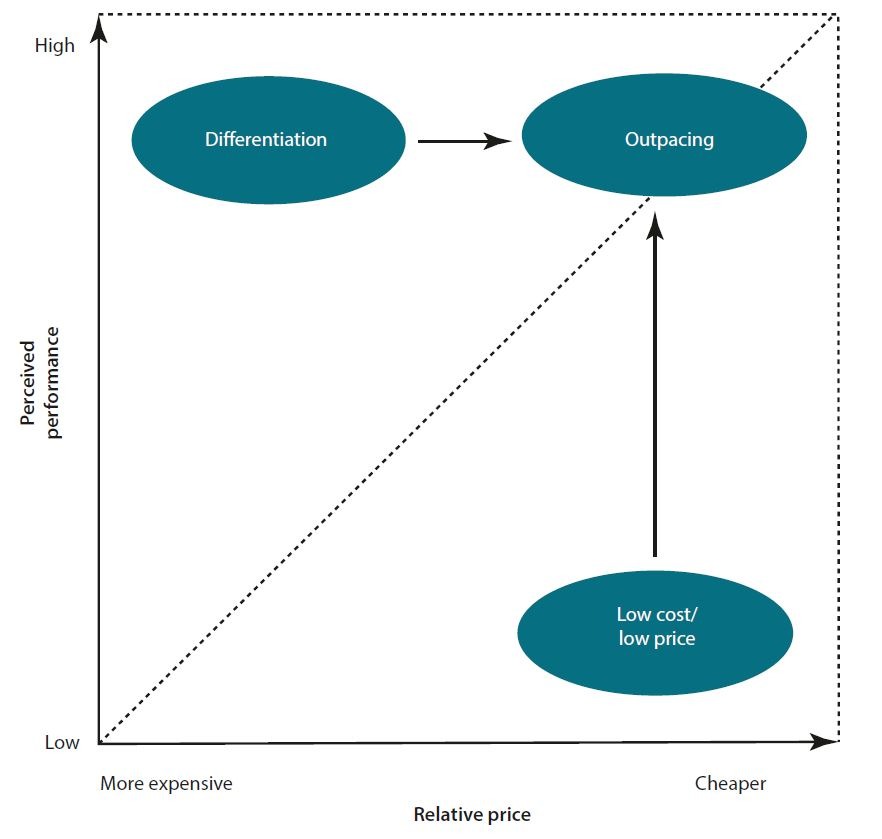

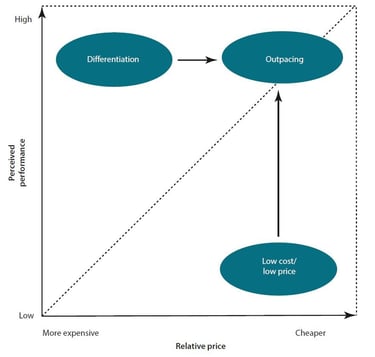

As circled above, the first step in phase two is to select a Strategic Option – a strategy type. To do this, Jelassi et al. (2014) refer to the strategy option model by Hungenberg, H. (2014), which is shown in the following figure. For business strategy selection, there are three major options: Differentiation strategy, Cost Leadership strategy, and if to pursue both, the Outpacing strategy. Their differences are better told by the figure below.

It is worth noting that what matters here is not to choose the ‘right’ option, but to ‘find a comfortable market position where the business can enjoy a competitive advantage’ (Jelassi et al., 2014). A second note is that for the Differentiation option, the sources of differentiation can be either tangible (quality, speed, product range, etc.) or intangible (brand, goodwill, etc.). You will see this again in the next section when we talk about integrating tangible/intangible resources to create causal ambiguity.

Now, the authors made another brilliant connection here: to better pursue any of the three strategic options, we need to consider the distinctive underlying Resources and Capabilities owned by a business. This links to Hungenberg’s (2014) Resources and Capabilities view on e-business competencies. Because the topic is very important, we will discuss it in an individual section coming next.

2. The Resource and Capability View on Competitive Advantage

So, now we shift our focus to the topic of Competitive Advantage. The logic is that to succeed in any of the three previously mentioned strategic positions, the business needs to have a competitive advantage. A competitive advantage comes from the business’ competencies. So, the question we try to answer in this section is: what is a digital business’ competency?

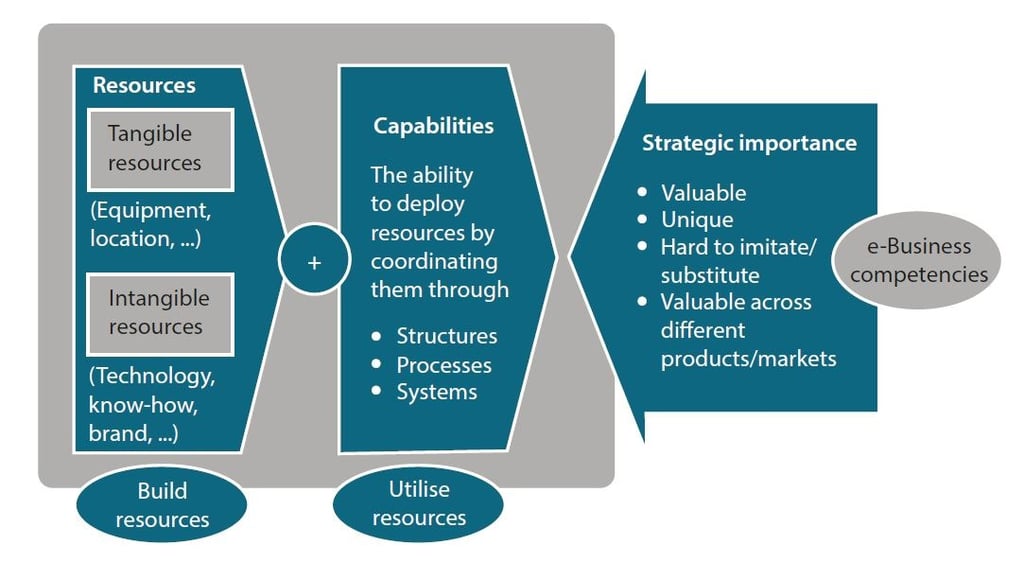

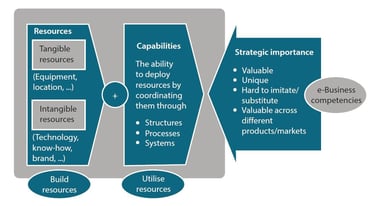

From the resources and capabilities approach (Hungenberg H., 2014), the concept of business Competence is defined as the ‘combination of resources and capabilities’. Resources can be either tangible or intangible, while Capabilities represent the skills of a firm to use its resources efficiently and effectively. This is demonstrated in the following model.

The above model shows a detailed view of the internal contributors to a company’s competence: resources and capabilities. It is worth noting that we also need to consider external factors. Ghemawat and Rivkin (1998) believe that competitive advantage is an outcome systematically influenced by both internal and external aspects (link to phase one analyses findings).

Therefore, the reality is that while a competitive advantage originates from internal resources and capabilities, it is also shaped by external factors, such as the competitive environment represented by Porter’s five forces and PESTLE. So, a decision-maker needs to organize internal and external aspects strategically and holistically. Creating competitive advantage is not about achieving lower costs or convenience, it is a matter of adaptability and strategic fit.

A Strategic Fit is created when the company can align strengths with opportunities while eliminating weaknesses to avoid threats. I do feel this idea still appears to be a bit conservative, so it is worth mentioning Hamel and Prahalad (1993)’s extended concept of Strategic Stretch. The latter explains the possibility of creating new market opportunities using competencies.

I believe Strategic Stretch is more closely related to a digital business transformation as the result tends to bring in new market opportunities. In the LSP’s example, an IT database approach to translation workflow will likely open up doors for translating highly repetitive and structured materials. These would have been difficult to deal with using manual translation without digital means.

Least but not the last, we need to discuss what is Core Competency and how to sustain it. This will carry us to our last topic of an implementation roadmap in the next section. According to Jelassi et al. (2014), a Core Competency is defined as a competency with the following characteristics:

1) Valuable,

2) Unique for value creation,

3) Hard to imitate, and

4) Reusable across functions/markets.

Here we will only focus on the third characteristic: hard to imitate. How to create barriers to imitation is very important in today's digital business strategy as a unique and valuable competency can be easily imitated across the Web. Jelassi et al. (2014) point out that there are several methods a digital business can use to protect its core competency. Among them, I believe the most important ones are:

1) Aligning activities across multiple functions/channels, and

2) Causal ambiguity.

First, competencies achieved through a unique fit between business activities are difficult to imitate. It is impossible for another business to acquire the same competency by imitating only one activity. Causal Ambiguity can also help an organization sustain its competencies. Causal Ambiguity means that the business can build up competencies based on a complex, multidimensional mix of sources. As explained previously, the sources can be both tangible and intangible. Even a person in the incumbent company may not have a clear understanding of the complex interplay between the factors leading to their own competencies.

With these two methods, a digital business is more likely to sustain its competencies in today’s digital world. A digital transformation of a business process inevitably involves some degree of integration across different functions and resources. So next, we will move on to the last 'implementation' phase - the digital transformation process.

3. A Roadmap of Digital Business Transformation (Phase Three)

Jelassi et al. (2014)’s idea of using cross-function alignments and causal ambiguity to build up inimitable competencies appeals to me a lot. In particular, I related the ideas to my experience leading a digital transformation project at a previous employer. I also recall a video from a student’s lecture material (source not found), in which the speaker tried very hard to convince listeners that ‘digitalization’ does not mean simply moving existing procedures online.

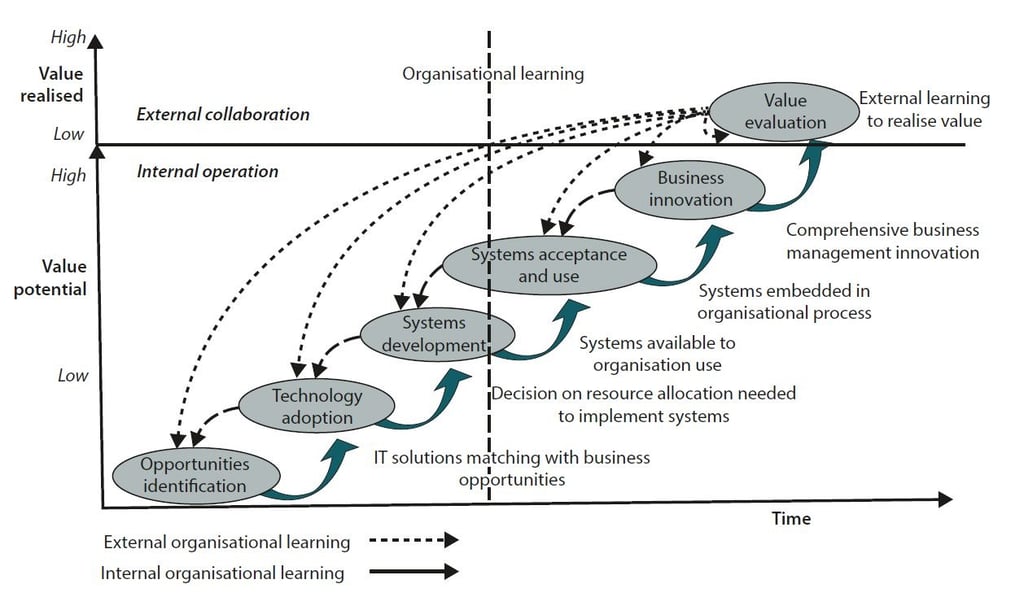

Digitalization means bridging existing processes or even creating new ones that go parallel to the existing procedure. It is not simply a connecting or converting process. From my experience, a digital business transformation process inevitably involves integration. The good thing is, the integration in turn empowers the business to create new competencies that are not only inimitable, but can also bring in new market opportunities (strategic stretch). This explains why nowadays businesses are interested in 'moving' things online, or onto the cloud. Even clearer, Jelassi et al. (2014) further quote a framework for the digital transformation process, which accurately represents my experience and thinking.

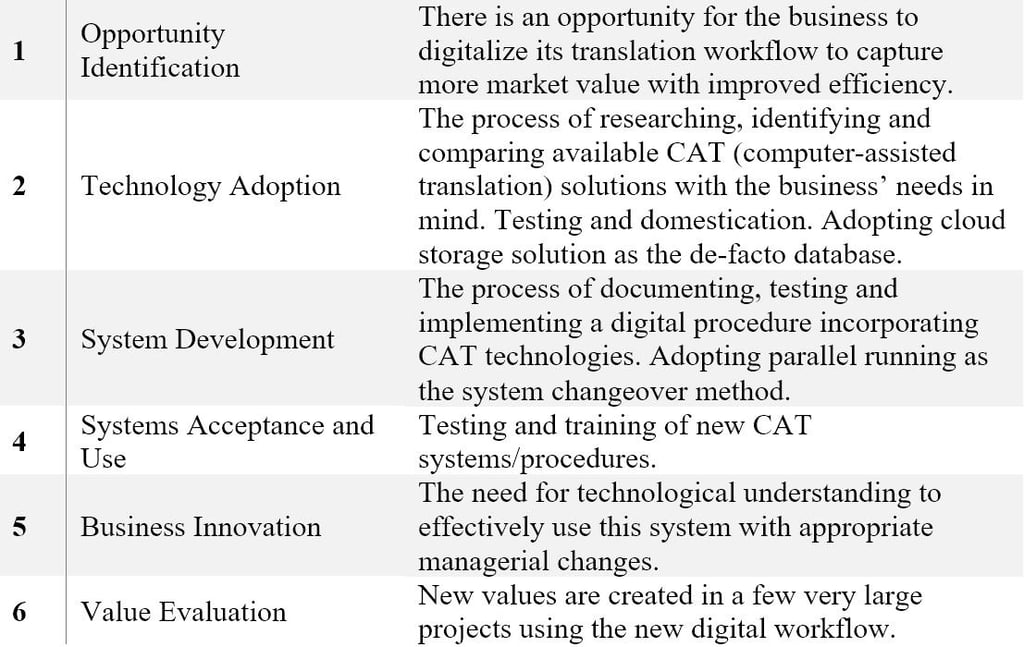

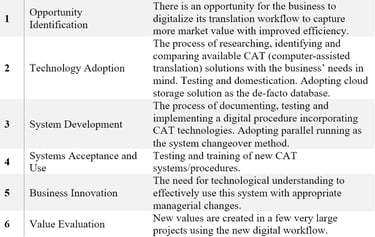

This is a model is originally proposed by Wu and Liu (2010) under the name of the ‘E-business Capability Model’. I would rather regard it as a roadmap for digital business transformation. Referring to the previously mentioned LSP example, we can connect its conceptual steps to my real-life business digitalization experience in the following table.

To me this model is truly fascinating. While other steps are quite self-explanatory and straightforward, I would like to emphasize on few related thoughts based on my personal experience: the 5th step above (business innovation) is often underestimated in a digital business transformation process. I am delighted to see that Jelassi et al. (2014) shared this insight by pointing out that ‘Businesses should be careful when implementing new e-business strategies. Not only might new strategies deplete firm resources, but they may also lead to fundamental changes in the organizational structure and processes’. Even with the new digital solution ready, the management should pay attention to potential conflicts and misalignments between new and old strategies.

In nature, business analysts, system analysts, and data analysts are supportive roles. They may mostly focus on the first 4 steps at the bottom on this roadmap. The management, however, may or may not understand that the system/tool deployed at the end of those steps does not guarantee their digital transformation’s success. There will be a further need for the management to internalise the digital solution into the existing processes, structure and conventions.

To Conclude

In this article, I explained a comprehensive model (Jelassi et al., 2014) that connects several seemingly segmented analytical frameworks and models. The framework forms a theoretical foundation for digital business transformation. We started in section 1 with the Strategic Analysis phase, where I demonstrated how to use SWOT Metrix to unite findings from PESTLE, Porter’s Five Forces and the conventional SWOT quadrants. The findings are also formative to our examination of business competency concepts in phase two.

In section 2, I introduced the second phase of the above framework, focusing on two key components: Strategic Options and Sustaining Competitive Advantage. From there, we went further to examine the Resource and Capability view on competitive advantage. Resources and capabilities are the internal contributors to a firm’s competence. We also acknowledge the external factors analysed in phase one as external influencers to shape the firm's competency. Therefore, a holistic mindset is needed to establish inimitable competency with consideration of strategic fit between both external and internal factors. We also discussed a related concept of strategic stretch.

To answer the question of how to sustain competitive advantage, we identified that one of the most important characteristics of core competency is its inimitability. There are two important methods to achieve this: across-function alignment and integration with causal ambiguity. The discussion then became a starting point for section three – implementing digital business transformation. From my experience, integration or bridging is unavoidable in a business' digitalization.

Therefore, in section 3, we present a roadmap model for digital business transformation. The fascinating model perfectly reflects my previous experience at work. I further agree with Jelassi et al. (2014)’s appeal for the management to note that adopting a digital solution does not mean simply moving existing processes online. Digitalization may bring impact organizational structure and processes. This is reflected by the ‘Business Innovation’ step in the road map, calling for management innovation after adopting a digital solution.

This article is very theoretical and only informs practice from the management point of view. From the practical perspective, I would relate to the innovative and design thinking concepts, which may be a good topic for my next blog article.

References

Cadle, J., & Turner, P. (2014). Business Analysis Techniques - 99 essential tools for success (2nd ed.). The Chartered Institute of IT.

Ghemawat, P., & Rivkin, J. W. (1998). Creating competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review.

Hungenberg, H. (2014). Strategisches Management in Unternehmen. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Jelassi, T., & Martínez-López, F. J. (2014). Strategies for e-business: Concepts and cases on value creation and Digital Business Transformation (4th ed.). Springer.

Wu, J.-N., & Liu, L. (2010). E-business Capability Research: A systematic literature review. 2010 3rd International Conference on Information Management, Innovation Management and Industrial Engineering.

Disclaimer:

This blog article is not written under any funding, nor is written for any financial gains. Please leave a message in the ‘Contact Me’ section if you want me to remove it for any reason.